home

about

artists

exhibitions

press

contact

purchase

home

about

artists

exhibitions

press

contact

purchase |

|

AUGUSTE RODIN Documents and Press AGREEMENT 1. PartiesThis is an agreement by and between Gruppo Mondiale Est. and Robert Jean Crouzet. 2. PurposeThe purpose of this agreement is for Gruppo Mondiale to purchase all rights, title, and interests from Robert Jean Crouzet in those certain Auguste Rodin plasters listed below. Robert Jean Crouzet agrees to transfer forever all interests, rights, title as well as any multiples, molds, photos, commercial leads for the following list of items, and agrees not to reproduce or create any works of art from these items. 3. Items1. The Great Thinker, 1903 (1,8 x 1,8 x 1,413 m) 2. The Medium Thinker, 1880 (72 x 45 x 56 cm) 3. The Hand of the Thinker (great size) 4. The Hand of the Thinker (medium size) 5. The Age of Bronze, 1887 (medium size, 105 cm) 6. The Age of Bronze, 1887 (small size, 65 cm) 7. Torso of Walking Man 8. Walking Man, 1877 – 1911 (85 x 28 x 58 cm) 9. Head of St. John the Baptist, 1879 (38 x 38,5 x 26,4 cm) 10. Head of Eustache de Saint Pierre, 1886 (33 x 21,3 x 24,8 cm) 11. Eternal Spring, 1884 (67 cm) 12. Eve, 1881 (72 cm) 13. Torso Morhart (42 cm) 14. Nijinski (34 cm) 15. Cariatide a la Pierre, 1880 – 1881 (43,5 x 32 x 30 cm) 16. Study of Feminine Torso (30 cm) 17. Danaid, 1889 (23 cm) 18. Bust of Age of Bronze, 1887 (28 cm) 19. Bust of Age of Bronze (53 cm) 4. Warranties Robert Jean Crouzet warrants that he has the right to transfer ownership of the items listed above. He also warrants that the items are authentic with correct measurements and are in good condition. 5. Terms and Conditions Gruppo Mondiale agrees to pay to Robert Jean Crouzet the sum of US$ 3,000,000 (three million US Dollars) for all right, title and interest in the items listed in paragraph 3 above. The sum should be transferred directly to Robert Jean Crouzet, and he will transfer directly the control and possession of aforementioned items to Gruppo Mondiale Est. 6. Confidentiality This agreement is intended to be a confidential agreement by and between the parties, as such, it is agreed that all of the terms, conditions, items, and transfers shall be held in the strictest confidence, and will not be disclosed, discussed, or communicated to any party, entity, or agency without the prior written permission of all parties. 7. Validity In the event any provision of this agreement shall be held to be invalid, the same shall not affect in any respect whatsoever the validity of the remainder of this agreement. 8. Agreed Damages In the event of the failure of any party to this agreement to perform as agreed the injured party shall receive double compensation for his loss. Signed and agreed upon: this _________ day of _____________, 1997. __________________________ ________________________ Gruppo Mondiale Est. Robert Jean Crouzet

AGREEMENT (Revised, February 2000) 1. PartiesThis is an agreement by and between Gruppo Mondiale Est. and Robert Jean Crouzet. 2. PurposeThe purpose of this agreement is for Gruppo Mondiale to purchase all rights, title, and interests from Robert Jean Crouzet in those certain Auguste Rodin plasters listed below. Robert Jean Crouzet agrees to transfer forever all interests, rights, title as well as any multiples, molds, photos, commercial leads for the following list of items, and agrees not to reproduce or create any works of art from these items. 3. Items1. The Great Thinker, 1903 (1,8 x 1,8 x 1,413 m) 2. The Medium Thinker, 1880 (72 x 45 x 56 cm) 3. The Hand of the Thinker (great size) 4. The Hand of the Thinker (medium size) 5. The Age of Bronze, 1887 (medium size, 105 cm) 6. The Age of Bronze, 1887 (small size, 65 cm) 7. Torso of Walking Man 8. Walking Man, 1877 – 1911 (85 x 28 x 58 cm) 9. Head of St. John the Baptist, 1879 (38 x 38,5 x 26,4 cm) 10. Head of Eustache de Saint Pierre, 1886 (33 x 21,3 x 24,8 cm) 11. Eternal Spring, 1884 (67 cm) 12. Eve, 1881 (72 cm) 13. Torso Morhart (42 cm) 14. Nijinski (34 cm) 15. Cariatide a la Pierre, 1880 – 1881 (43,5 x 32 x 30 cm) 16. Study of Feminine Torso (30 cm) 17. Danaid, 1889 (23 cm) 18. Bust of Age of Bronze, 1887 (28 cm) 19. Bust of Age of Bronze (53 cm) 4. Warranties Robert Jean Crouzet warrants that he has the right to transfer ownership of the items listed above. He also warrants that the items are authentic with correct measurements and are in good condition. 5. Terms and Conditions Gruppo Mondiale agrees to pay to Robert Jean Crouzet the sum of US$ 3,175,000 (three million one hundred and seventy five thousand US Dollars) for all right, title and interest in the items listed in paragraph 3 above. The sum should be transferred directly to Robert Jean Crouzet, and he will transfer directly the control and possession of aforementioned items to Gruppo Mondiale Est. 6. Confidentiality This agreement is intended to be a confidential agreement by and between the parties, as such, it is agreed that all of the terms, conditions, items, and transfers shall be held in the strictest confidence, and will not be disclosed, discussed, or communicated to any party, entity, or agency without the prior written permission of all parties. 7. Validity In the event any provision of this agreement shall be held to be invalid, the same shall not affect in any respect whatsoever the validity of the remainder of this agreement. 8. Agreed Damages In the event of the failure of any party to this agreement to perform as agreed the injured party shall receive double compensation for his loss. Signed and agreed upon: this _________ day of _____________, 1997. __________________________ ________________________ Gruppo Mondiale Est. Robert Jean Crouzet

CONFIDENTIAL IRREVOCABLE CONTRACT OF SALE/EXCHANGE PARTIESThis agreement is by and between Jacques Marcoux of Paris, France, and Gary Snell, acting as agent for Gruppo Mondiale. RESPONSIBILITIES OF PARTIESA) Gruppo Mondiale agrees to give to Jacques Marcoux the following: 1) Two (2) American saddles in leather and silver with an agreed value of eighty forty thousand US Dollars ($40,000) 2) One (1) group of jewelry in gold and diamonds with an agreed value of eighty thousand US Dollars ($80,000) 3) One (1) album of original photos signed by David Hamilton valued at forty thousand US Dollars ($40,000) 4) A Breguet wrist-watch valued at two hundred thousand US Dollars ($200,000) 5) One million six hundred and ninety thousand US Dollars ($1,690,000) B) In exchange for all the aforementioned items, Jacques Marcoux agrees to transfer to Gruppo Mondiale the following original plaster proofs after Auguste Rodin from the foundry of Rudier with the original expertise from Phillippe Cezanne as follows: 1) The Grand Iris, 94 cm, valued at five hundred thousand US Dollars ($500,000) 2) The Grand Age of Bronze, 183 cm, valued at five hundred thousand US Dollars ($500,000) 3) The Grand Eve, 173,5 cm, valued at five hundred thousand US Dollars ($500,000) 4) The Grand Kiss, 87,5 cm, valued at five hundred fifty thousand US Dollars ($550,000) C) Jacques Marcoux warrants that no duplicate plasters or molds have been made from the above referenced plasters. WARRANTYJacques Marcoux warrants that he has the right to transfer all right, title, and interest of property referenced in this document, and by signing below does so. DAMAGES This contract should be considered as irrevocable with agreed damages of one million US Dollars to be paid by the breaching party to the non-breaching party. Damages should also apply to confidentiality breaches. CONFIDENTIALITYThis contract is considered to be a confidential agreement and not to be discussed, disclosed or communicated to any party, entity or agency without the prior written permission of all parties. In the event confidentiality should be breached, it is agreed that the breaching party shall pay one million US Dollars damages plus any consequential damages to the non-breaching party. AMENDMENTSThis contract can only be amended in writing and agreed by the parties. July 4, 1996 ______________________________ ___________________________ JACQUES MARCOUX GRUPPO MONDIALE EST.

CONFIDENTIAL IRREVOCABLE CONTRACT OF SALE/EXCHANGE (Revised, February 2000) PARTIESThis agreement is by and between Jacques Marcoux of Paris, France, and Gary Snell, acting as agent for Gruppo Mondiale Est.. RESPONSIBILITIES OF PARTIESA) Gruppo Mondiale agrees to give to Jacques Marcoux the following: 1) Two (2) American saddles in leather and silver with an agreed value of forty thousand US Dollars (US$40,000) 2) One (1) group of jewelry in gold and diamonds with an agreed value of eighty thousand US Dollars (US$80,000) 3) One (1) album of original photos signed by David Hamilton valued at forty thousand US Dollars (US$40,000) 4) A Breguet wrist-watch valued at two hundred thousand US Dollars (US$200,000) 5) An apartment located at Blv. Maurice Barres 9200 Neuilly, with an agreed value of one hundred seventy-thousand US Dollars (US$170,000). 6) Two (2) houses located in Providencialles Turks and Caicos with an agreed value of two hundred twenty-thousand US Dollars (US$220,000) 7) Two million two hundred thousand US Dollars (US$2,200,000) B) In exchange for all the aforementioned items, Jacques Marcoux agrees to transfer to Gruppo Mondiale Est. the following original plaster proofs after Auguste Rodin from the foundry of Rudier with the original expertise from Phillippe Cezanne as follows: 1) The Grand Iris, 94 cm, valued at six hundred and fifty thousand US Dollars (US$650,000) 2) The Grand Age of Bronze, 183 cm, valued at seven hundred and fifty thousand US Dollars (US$750,000) 3) The Grand Eve, 173.5 cm, valued at seven hundred and fifty thousand US Dollars (US$750,000) 4) The Grand Kiss, 87.5 cm, valued at eight hundred thousand US Dollars (US$800,000) C) Jacques Marcoux warrants that no duplicate plasters or molds have been made from the above referenced plasters. WARRANTYJacques Marcoux warrants that he has the right to transfer all right, title, and interest of property referenced in this document, and by signing below does so. DAMAGES This contract should be considered as irrevocable with agreed damages of one million US Dollars to be paid by the breaching party to the non-breaching party. Damages should also apply to confidentiality breaches. CONFIDENTIALITYThis contract is considered to be a confidential agreement and not to be discussed, disclosed or communicated to any party, entity or agency without the prior written permission of all parties. In the event confidentiality should be breached, it is agreed that the breaching party shall pay one million US Dollars damages plus any consequential damages to the non-breaching party. AMENDMENTSThis contract can only be amended in writing and agreed by the parties. July 4, 1996 ______________________________ ___________________________ JACQUES MARCOUX GRUPPO MONDIALE EST

FAX TRANSMISSION From: GARY SNELL – GRUPPO MONDIALE EST. To: Musee Rodin, Paris. Attn. Stephanie Le Follic Fax Number: 0033 1 44 18 61 10 Number of Pages: 1 (incl. cover page) Date: 11.05.1999 Subject: Meeting with Mon. Vilain and Ms. Le Folic Dear Ms. Le Follic, You have asked me to give you two possible dates next week for a potential meeting. I would propose Wednesday afternoon (November 10) from 2 pm onwards , Thursday November 11, your choice at any time, or as an alternative, but less preferred, Friday morning either 9 or 10 o’clock. I would prefer your response to be sent via email to Gruppomondiale@libero.it , as I will be travelling for the next few days and it will be the easiest way for you to communicate directly with me. I will confirm with you when I have your response. I am looking forward to meeting you and Mon. Vilain. Sincerely, Gary Snell GS:crm

Mr William Moore

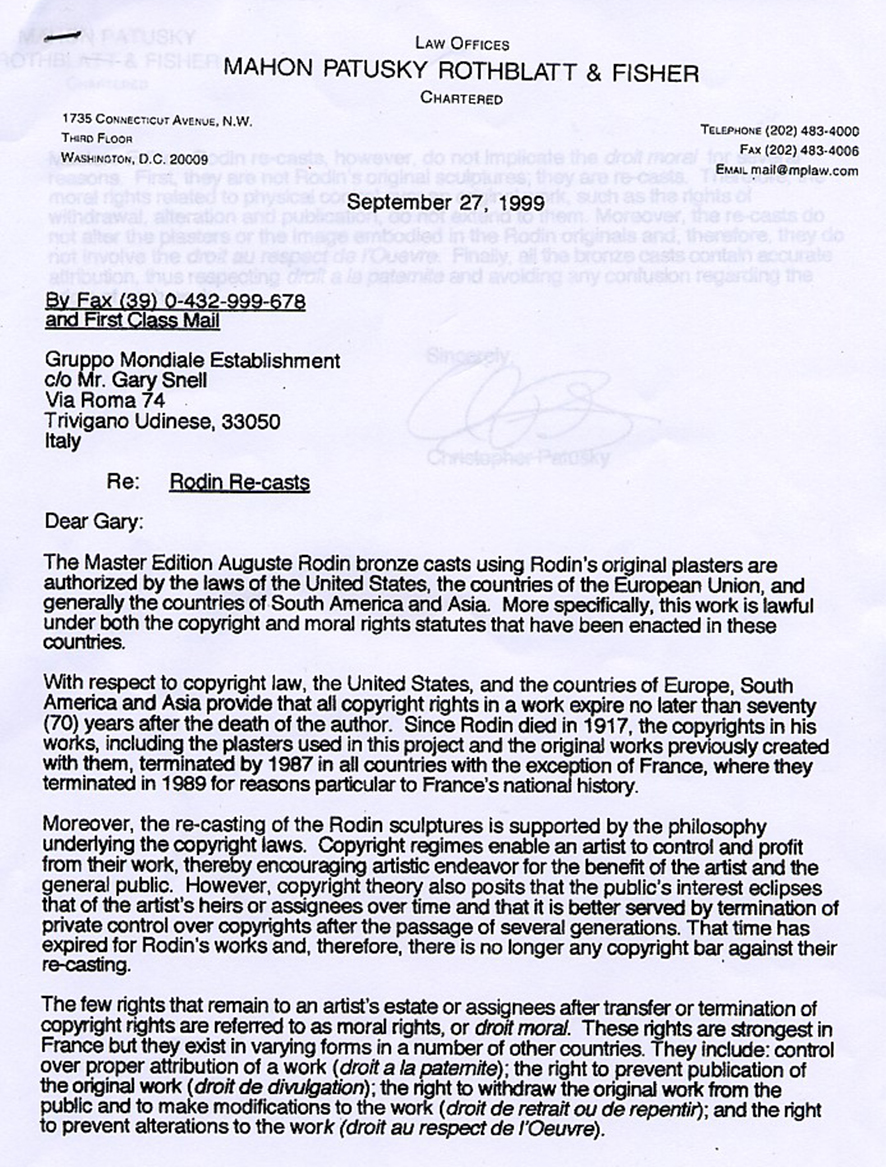

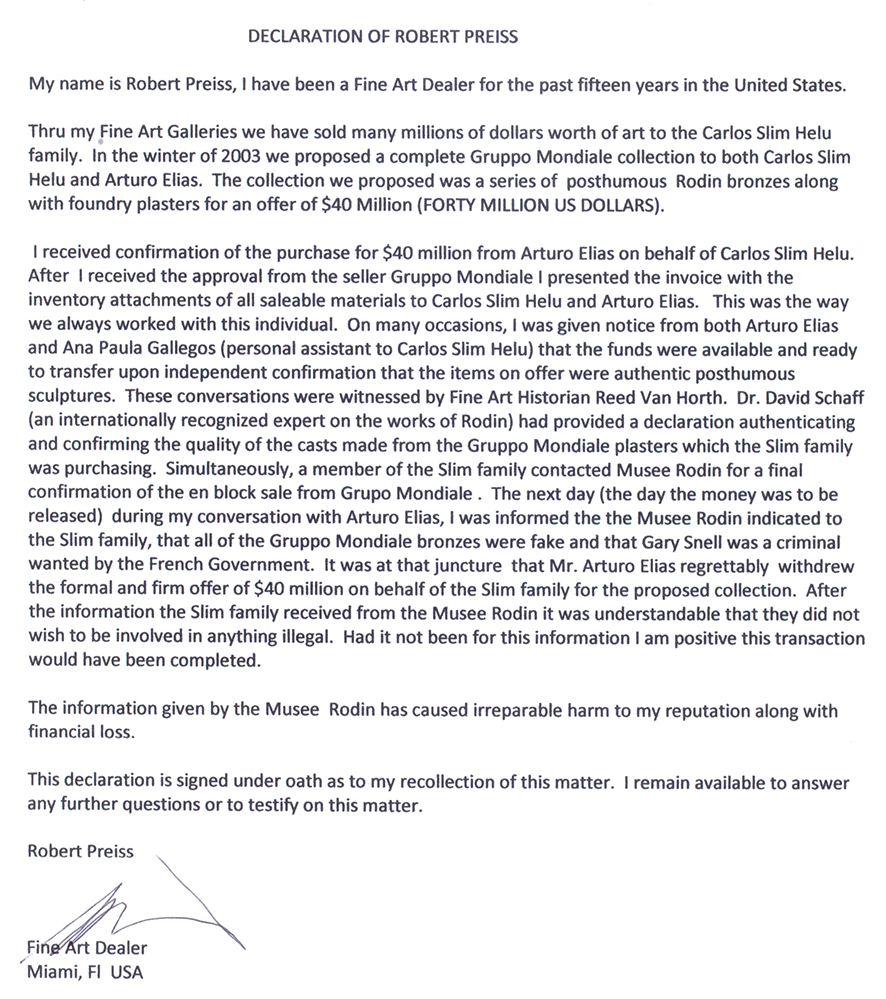

http://www.bbeyondmagazine.com/rodin-art-gary-snell-france-legal-case/ A David v. Goliath battle has been quietly playing itself out in the French courts for the last 17 years in the curious case of Auguste Rodin’s posthumous bronze casts and the right to produce, exhibit and sell them. As is the case with all art-related disputes, this is primarily about money (Musée Rodin generates an income from the production and sale of its bronzes). Take one wealthy collector, a state-owned museum, and the rights to the work of the most recognized sculpture artist of modern times, and you end up with a fully fledged nuclear war in the rarefied world of high art. The story began when American-born Gary Snell, a prolific collector of Deco-style art, was approached by an art dealer with an offer to acquire a few of Rodin’s foundry plasters. Realising the potential, Snell joined forces with a Liechtenstein entity, Gruppo Mondiale, to produce a very limited series of bronzes, In order to understand the significance of this offer, we need to digress some and explain to the reader what “foundry plaster” means. Auguste Rodin created most of his works first out of clay. The clay was kept moist until he was happy with it, after which he would instruct a mold maker to prepare a mold known as a moule à bon-creux. The very first plaster from the moule a bon creux is referred to as the “original plaster”. The moule à bon-creux, or the “negative”, would be destroyed after use (the few remaining ones have deteriorated over time). The positive form was sent to the foundry to have it cast in bronze and is henceforth referred to as “the foundry plaster” (the foundry plasters are made from a new mould, itself made from the original plaster). Alexis Rudier’s foundry was Rodin’s principal foundry and has, therefore, the best link to the artist. Rodin Intellectual Property: A Seemingly Straightforward Application of the Berne ConventionAt the end of the 1960s the definition of an original work of art was enshrined in a law (Article 98A, Appendix III, formerly Article 71, of the General Tax Code) which provides that “Are considered as works of art […] limited edition print carvings limited to eight copies and controlled by the artist or his successors […]”. This regulation means that a sculpture is considered as an original work of art so long as it is limited to 8 copies. Thus, Musée Rodin had the right to produce only 8 copies that are considered “original bronzes”; all further casts being “posthumous bronzes”. The Parisian institution was founded in 1919 as part of a condition in Rodin’s will that granted the French State ownership of his collected works. Under French law, and in line with the near-universally adopted Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, the right to enforce copyright expires 70 years after an artist’s death. Thus, in 1987, 70 years after Rodin’s death, the museum were no longer able to enforce the copyright that had been bequeathed to them. After ’87, all of the artist’s works reverted to the public domain with the exception of the Moral right (the right to be identified as the creator of the work and to object to any distortion which would be prejudicial to the artist’s reputation). Musée Rodin holds this “moral right” and so has cast a number of unchallenged posthumous bronzes, many of which are sold at auction with a tag price to match. A recent auction saw an original posthumous Rodin bronze, Penseur, Petit Modele, sell for $2,775,505. Snell, it has to be pointed out, is obsessive about researching and documenting detail. He established that the plasters he was offered had been acquired, for the most part by a single collector, directly from George Rudier, the former foundry owner’s nephew who had taken over in 1954. B Beyond interviewed Gary Snell who elaborates on his initial interaction with Musée Rodin and the chronology of the subsequent dispute: “Once I understood the significance of the foundry plasters, I went to Musée Rodin and asked them to authenticate them. The museum confirmed that they were indeed foundry plasters from the Rudier foundry. “Word spread that I was buying Rodin plasters and in the early 90’s, when the IP rights fell back into the public domain, everyone who had something to sell would approach me. “I would approach Musée Rodin to similarly authenticate everything unless I bought it from Christie’s or Sotheby’s.” Snell spent 5 years researching the casting technique used by Rodin’s foundry for the production of the bronzes. He then found an Italian foundry that was able and willing to replicate this technique in a minute detail, including the complex and onerous patina process. Each bronze, he says, takes 3 months to cast and refine. “To begin with, I bought the plasters for my personal collection only, however, I soon started getting offers to exhibit the bronzes at museums around the world. “My relationship with Musée Rodin at the beginning was amicable and I had regular exchanges with their former archivist, Alain Beausire, as well as the then museum director.” In fact, Beausire endorses the Snell plasters quite unequivocally, in written articles on the subject, notably in a Le Journal Francais piece. “When I told them of my intention of producing a limited edition of bronzes for the purpose of exhibiting and selling them, they raised no objection.” The Musée Rodin itself does, of course, also exhibit posthumous Rodin bronzes, as do a number of reputable institutions around the world, namely the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, the Cantor Arts Center at the prestigious Stanford University, The Glenbow Museum in Calgary, the National Gallery in Berlin, The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. The main difference is that Musée Rodin also sells these bronzes in order to fund itself. The relatively cosy relationship Snell enjoyed with the Musée Rodin ended abruptly in 2001 when the Royal Ontario Museum staged an exhibition of his bronzes. “The then ROM curator decided to draw attention to the event by suggesting our exhibition of Rodin bronzes rivalled in quality the Musée Rodin bronzes.” This assertion spurred the Musée Rodin into action and a flurry of articles appeared in the main Canadian newspapers at the time, setting the ”line in the sand” of the conflict in the making. The following statement appears in the Globe and Mail in 2001: While critics — including the Musée Rodin in Paris, the executors of the Rodin estate — have not denied that the pieces are foundry plasters, they have argued that they were made 40 or 50 years after Rodin’s death and should be regarded as, variously, counterfeit, “too far removed from Rodin’s hand,” or unauthorized reproductions. Globe and Mail, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/rom-extends-rodin-exhibition/article4158259/ The Musée Rodin followed on by starting a lawsuit against Snell alleging counterfeiting and citing a criminal action filed against Snell by the French State. Bizarrely, the State didn’t pursue the action nor were Snell’s lawyers able to access the court file. Incensed, Snell instructed a legal team to file his own action against the French State in 2007 – for dysfunction of the public service of justice. By 2014 Snell, along with Gruppo Mondiale, a Liechtenstein-based company partnered with Snell’s company Euro Group, appear to have prevailed: the French court delivered a judgment that the French State had no jurisdiction over the Snell bronzes and that French law was therefore not applicable. Given that the Musée Rodin had previously documented both the provenance and worth of bronzes, Snell argues that, “Musée Rodin alleged that the bronzes were counterfeit simply because they had not authorised them, in what is, essentially a commercial dispute.” Things turned more sinister in 2016, when the Appellate Court simply overturned the previous judgment and found that the French Court did, in fact, have jurisdiction, and that French law was applicable, after all – in spite of the already established facts. At this stage of the hostilities Musée Rodin appear to have taken a new tack, now insisting that the moulds were French and therefore the bronzes were subject to a particular French customs tax code that is only applicable in France. Snell is adamant that neither he nor the Italian foundry ever used any moulds from France, nor cast any bronzes in the country which renders the point moot. In any case, he asserts quite logically, the relevant French customs tax code is only applicable in France. “The court case has gone through the full gamut of challenges touching upon international and French intellectual property law, and the very particular French droit moral [moral right] law. We have used foundry plasters and original production techniques and given the bronzes proper attribution, so the droit moral should not be an issue either. “Ultimately, this has the hallmark of a commercial dispute over the right to exploit works in the public domain and to protect the income stream of Musée Rodin.” As far as Snell is concerned, the attempt to apply a French tax law outside of France is motivated by Musée Rodin’s “determination to retain a monopoly on selling posthumous Rodin casts and protect their profit margin”. The state-owned Rodin Museum is, of course, able to protract litigation ad infinitum. Snell, on the other hand, has to continue funding his own representation and has been doing so since 2001. The strategy of obliterating an opponent through years of legal wrangling is hardly new, even if the ethics of it are questionable. Stay tuned for the last act in the French State v. Snell saga as we report on it early 2019. Meantime, the Snell collection of Rudier plasters and posthumous bronzes is a unique and remarkable one, given the plasters’ undisputed provenance and the legal right to reproduce the works, just as Musée Rodin and its other illustrious counterparts in other countries do.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/after-18-years-two-art-dealers-sentenced-over-fake-genuine-rodin-sculptures Gary Snell, the US art dealer who tried to sell hundreds of copies of Rodin sculptures, has been sentenced to a one year suspended prison sentence and a €15,000 fine by the Paris court of appeal for having "counterfeited the work of the artist". During Snell’s trial last February, the state prosecutor, acting on behalf of the Musée Rodin, accused him of “shamelessly” using Rodin's name “to sell ‘fake-genuine' bronzes on an industrial scale." The case is considered exceptional because of the sheer number of works that Snell had cast in Vicenza, Northern Italy, which the court estimated to be around 1,700. According to the prosecution, each cast was offered for sale for an average of €40,000, the total being valued at €68m. On 17 April, the Parisian art dealer Robert Crouzet was also condemned by the court to a four-month suspended sentence for having sold 16 of Rodin’s moulds to Snell, including those of The Thinker, The Walking Man and Eve, in various sizes and formats. Along with Snell’s now-liquidated Liechtenstein-based company Gruppo Mondiale, Crouzet has been condemned to pay €500,000 in damages to the Musée Rodin, which holds the artist’s rights. It took 18 years for the Paris museum, which first filed the complaint in 2001, to reach this judgement in its favour—but it can still be submitted to the French High Court on appeal. In his will, Rodin left everything to the French State. However, his foundry, the Rudier Foundry, sold some of his original plaster moulds, and it was these that Snell bought to produce his copies, claiming that it was free to do so now that the artist’s work is no longer under copyright. But Snell’s bronzes were not marked as “reproductions”, as required by French law, and some of them even bore the signature of Rodin and the Fonderie Rudier mark, instead of that of the Italian foundry. According to the prosecution, buyers could have easily have been led to believe they were acquiring a genuine Rodin for a bargain price. Snell, who accused the Musée Rodin of “protecting its monopoly“, says that the word “reproduction“ would have prevented him from selling the works on the US market. His lawyer, Christian Beer, pleaded that the French rules do not apply abroad and that his client never sold his pieces in France. He also said the criminal investigation had “totally ruined” the US dealer. However, the legal expert Gilles Perrault also explained in court that the very low quality bronze copies “betrayed” the spirit of Rodin, distorting his forms, cutting hands or heads from the figures and even inventing shapes he never made. Hundreds of these forgeries were seized in Vicenza and in Toronto where they were being sold to a local gallery.

http://www.bbeyondmagazine.com/rodin-museum-gary-snell-intellectual-property/ A number of publications have written about the 17th April 2019 Paris Court sentencing of Gary Snell, an American collector, on counterfeiting charges for reproducing Rodin bronzes from original plasters he acquired in the 1980s/1990s. It is worth noting that: 1. The judgement directly contradicts the Berne Convention and its application of Intellectual Property Rights. The convention, to which France is a signatory, stipulates that the copyright of a work of art or literature expires 50- 70 years after the author’s death and reverts to the public domain thereafter. 2. If Snell is in breach of copyright or counterfeiting, then so would be countless publishers of works of art, literature, etc. by famous authors. The entire canon of Western literature would not be translated and reproduced and Van Gough’s “Sunflowers” wouldn’t appear on post cards 3. The Musee Rodin v. Gary Snell and various other defendants legal dispute has been going on for two decades during which time Gary Snell has won case after case in different jurisdictions including France. In this last (or latest, pending possible appeal by Snell) round, Musee Rodin, who appealed an earlier court judgement, won on moral right and counterfeiting charges 4. Given that the Snell bronzes are direct reproductions from foundry plasters authenticated by Musee Rodin, finding against Snell on counterfeiting is clearly flawed or partisan/biased in favour of Musee Rodin, a state-sponsored institution 5. Further, Musee Rodin has never contested the authenticity of the plasters, nor can it. In fact, Musee Rodin itself does exactly the same, i.e. reproduces Rodin’s works for the purpose of selling them. Some of these Musee Rodin reproductions are made in resin and it may be argued that in itself is a distortion of the artist’s legacy. 6. The French court has also chosen to level an ethical criticism of Snell, namely that he has profited from Rodin’s legacy. If profiting from an author’s legacy were unethical, the world would be a culturally poorer place, with no stage productions, no books, no sculptures perpetuated in any form by those willing to take a commercial risk for profit 7. It follows that the dispute between Musee Rodin and Gary Snell is an entirely commercial dispute, often presented as an attempt to protect the legacy of the French sculptor or the national heritage. In that Musee Rodin intends to keep its monopoly on reproducing Rodin’s works and on selling them, from resin gift shop merchandise to large bronzes via auction houses, it can hardly claim a higher moral ground in relation to anyone doing the same for personal gain 8. Lastly, Gary Snell has donated the entire proceeds of selling the bronzes he has produced from these authenticated plasters to charitable causes as well as funded his legal costs for close to 20 years. He is considering taking an appeal all the way to the European court of justice.

https://docplayer.net/65502515-The-museum-reportedly-refused-the-offer-but-also-reminded-the-applicable-legislation-on-the-matter-during-the-discussions.html 1) The RODIN museum’s complaint. On March 26th 2001, the director of the RODIN museum, a national public establishment of an administrative character placed under the authority of the minister of culture, filed a complaint against Jon Gary SNELL and «GRUPPO MONDIALE» an Italian based company domiciled in Lichtenstein for the following infractions: misleading advertising, counterfeit and fraud. The RODIN museum explained that Jon Gary SNELL and his company would cast bronze sculptures of the masterpieces of Auguste Rodin using foundry plaster casts instead of the original plaster casts while refusing to mark them as «reproductions». The museum added that the two defendants who had published a book entitled «Rodin plasters and bronzes» had organised in 2000, an exhibition in Venice and in Maastricht introducing «original plasters» and reproductions of some Auguste RODIN sculptures. Further investigation showed that other exhibitions allegedly took place in Bologna, Italy in 2000, in Mouscron Belgium in April 2001, in Toronto Canada in early 2002 and in Geneva Switzerland in 2003. Fifty-seven masterpieces were allegedly presented in the context of that last exhibition. The RODIN museum curators have visited the exhibitions held in Toronto and Geneva and have concluded that the pieces presented there couldn’t be considered as original pieces. The museum also specified that the company runs a website, www.rodin-art.com, on which are exposed 49 plasters introduced as original masterpieces of Auguste RODIN and sales of bronzes casted from those plasters are organised. The museum finally exposed the legal dispute opposing it to MACLAREN CENTER in CANADA which exposed 25 plasters introduced by it’s directors as foundry plasters and litigious sculptures all of those coming from the “GRUPPO MONDIALE” company. The litigious objects had been offered to the museum by donators who whished to benefit from a tax advantage. The RODIN museum explained that as early as November 1999, it had been approached by Gary SNELL who allegedly offered a partnership to not only publish the museum’s original bronzes but also to create bronzes for his own account which he refused to mark as “reproductions”. This mark is required by the French legislation. The museum reportedly refused the offer but also reminded the applicable legislation on the matter during the discussions.

On April 1st, September 13th and October 25th 1916, Auguste Rodin donated his property rights on his personal sculpture masterpieces including the original pieces, the casts, the copies or reproductions, the prints and the mouldings to the French State. The original pieces were composed of bronzes and marbles as well as 5 500 plasters itemised in the museum’s registry as inalienable French assets. The artist conditioned this donation to the creation of a museum, named after him and exposing his work, of which he would retain the leadership until his death. This donation was definitely accepted by the law of December 24th 1916. The article 10 of the law of June 28th 1918 recognises retroactively from November 18th 1917 on the civil personality and financial autonomy of the RODIN museum. Article 2 of the February 2nd 1993 decree attributes to the RODIN museum " the mission to make Rodin's work known and to enforce the moral right attached to it". Article 5 of the same decree indicates that the museum "proceeds to the creation of numbered original bronzes using plasters figuring in the collections" The work of Auguste RODI N fell into public domain in 1987. Therefore, the RODIN museum as well as anybody else can make reproductions of the sculptor's work on the condition that his moral right and the applicable legislation on the matter of original masterpieces and reproductions is respected. The legislation in question will be further discussed in the discussion part.

Two foundries appeared and were searched during the investigation. A complaint for an attempted extortion against Stuart MILLS was filed by Judith SECCOMBE HETT HAZEL, a rich American who wished to buy some Rodin pieces from the "GRUPPO MONDIALE" company. Stuart Mills has worked alongside Gary SNELL. The investigation led by Italian authorities shows that the company resorted to the services of the GUASTINI foundry located in Gambarella in the province of Vicenza. Meanwhile, the expert nominated by the investigating judge, after having examined the plasters and sculptures exhibited at the or detained by private individuals in Canada, indicated by way of mail to the MACLAREN CENTER that the plasters of the most certainly came from the GUASTINI foundry. The search and seizures of the bronzes, plasters and casts carried out during the summer of 2005 by the Italian riflemen in the presence of the French investigators and the expert aforementioned have led to the discovery of 93 casts and 56 bronzes most of them signed "RODIN" with many different numbering. The verifications demonstrated that "GRUPPO MONDIALE" manufactured the bronzes, attributed to Auguste Rodin by this foundry, since 1998. In his hearing, Mirko PAOLINI, the son and associate of the foundry's manager explained that Gary SNELL had claimed to be the owner of the casts and sculptures of RODIN used by his foundry and that he owned the rights deriving from this exploitation. He specified that every purchase was personally ordered by Gary SNELL, acting in the name of his company, "GRUPPO MONDIALE". He assured that the mention "Master Limited Edition" and a number were marked on every sculptures. He also declared that for 4 or 5 pieces, he had made plasters of casts before creating the bronzes and that it all had been billed to the ''GRUPPO MONDIALE" company. He hasn't been interrogated on the fact that three bronze sculptures wrapped and ready to be shipped wore no identification number. At his audience, Gary SNELL indicated that the sculptures were apparently wrapped up not for shipping purposes but to protect the chemicals usually used in the foundries. It is to be noted that all of the seized pieces were restored to the "GRUPPO MONDIALE" company in June 2008 after the decision of the Venetian Court of Appeals. The particularity of the casts seized in Italy led the expert to prescribe an investigation of the SILVA foundry settled in Wissous in the Essonne region. The search of October 2006 made it possible to discover 3 casts very similar to those found in Italy according to the expert. The expert indicated that: "the examination of 3 "ancient" casts... has made it clear that they have been made by the same people that made the French casts brought by Mr SNELL to the foundry GUASTINI. The materials used, the creating process using the same "tube à inox" method and the screeds and hulls configuration rule out any doubt on this matter. The exam of the inside of the casts made it possible to discover the name of their maker: Monsieur Bernard DE SOUZY." Nevertheless, the three casts discovered in the SILVA foundry have no connection to the pieces related to this case because they are casts of busts and not RODIN sculptures. The manager of the foundry, Possidonio Dos Santos Silvia explained that elastomer casts of the "Head of St John the Baptist" and the "Age d'Argain" had been given to him by Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY. The examination of the bills confirmed the existence of a relationship between him and the SILVA foundry. Nevertheless, the manager wasn't asked to elaborate on the casts discovered in his foundry. The search of Bernard POISON DE SOUZY's workshop led to the discovery of 2 bronzes, 14 plasters and 15 elastomer casts. Eight of those casts were seized after the expert deemed them to be identical to those found inside the GUASTINI foundry. Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY declared to have had contacts with Gary SNELL in 1997 and to have accepted to make a dozen casts in his SAINT OUEN workshop using plasters obtained from Mr SNELL. He explained that the elastomer casts strengthened by a glass fabric he made were marked as reproductions. He added that Gary SNELL, having recovered the plasters, brought them to Italy. He himself had had no influence over what had become of the plasters there. Such plasters marked with the word "reproduction" in marker have been found in his SAINT OUEN WORKSHOP. In a letter addressed to the investigating judge, he specified that he had made casts for 13 plasters including L'eternel printemps, Age d'Argain, Eve, L'homme qui marche, Le penseur, La tete d'Eustache de Saint Pierre, La tete de Saint Jean Baptiste, la caryatide a la pierre ... Furthermore, he said that the first three plasters were accompanied by a certificate of authenticity delivered by Philipe CEZANNE an expert. Only 6 of those masterpieces are mentioned in the "referral order".

Heard at a very late stage of the legal proceedings, Gary SNELL recognized without difficulty that the casting of the litigious masterpieces had occurred. He explained that the company GRUPPO MONDIALE allegedly obtained plasters of Auguste Rodin's sculptures outside of the French territory in the 1990's from different merchants and art collectors. Those transactions were made by way of bank transactions. Even if he denies having bought the casts directly from Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY, he admits to have indeed bought them from:

He also admits to have bought casts made by Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY from Robert CROUZET but declares that they haven't been used for technical reasons and not because they were marked as "reproductions". The first three persons alone have been heard in the legal proceedings, without any explanation as to why the other plaster merchants were not. Robert CROUZET explained that in 1996, he traded old paintings for 15 plasters from the RODIN foundry with Jacques MARCOUX. He then said to have met Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY with whom he wished to move to the United States to mould and sell Rodin’s sculptures there. Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY allegedly started to make casts and mould a few sculptures, all of them marked as reproductions. He then decided against the move to the US and introduced Gary SNELL to Robert CROUZET. A partnership contract is said to have been signed on March 26th 1998 between Mr CROUZET and “GRUPPO MONDIALE” represented by Gary SNELL, Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY and Galia MOUSSINA a friend of the later. The contract planned the sale of 15 plasters, bought from Jacques MARCOUX as well as a partial moulding of the torso of “L’homme qui marche”, made by Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY, to the “GRUPPO MONDIALE” for the sum of 600 000 $. Robert CROUZET added that to his knowledge, this 16th plaster couldn’t be a reproduction marked as such by the RODIN museum. In the contract, it is mentioned that: “Robert Jean CROUZET will accompany each plaster with a certificate of authenticity. The certificate will be given by Phillipe Cézanne attesting that each plaster comes from the RODIN foundry and meets all the standards of original RODIN sculptures.” It should be noted that Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY denies the existence of the original scheme as it is presented by Robert CROUZET but specifies that he started to make casts for the later from 1996 on. He added that Robert CROUZET acted as the owner of the plasters: “I didn’t feel he was linked with any other person that would make him the “holder by permission”. Robert CROUZET said he had then introduced Jacques MARCOUX to Gary SNELL. Jacques MARCOUX allegedly sold two plasters to the later by way of a complex contract which specified that Gary SNELL had to pay Robert CROUZET, who presumably sold an apartment located in Neuilly and a property in the Caïcos Islands for the price of 385 000 $. Robert CROUZET assured that the 16 plasters enumerated in the contract of March 26th 1998 had been picked up by Gary SNELL from his house in Neuilly-sur-Seine. At first, he indicated that he had delivered the 2 plasters bought from Jacques MARCOUX himself in regards of their relationship with the GUASTINI foundry. Then, in front of the investigating judge, he rectified that Gary SNELL got hold of the plasters in the Netherlands. Robert CROUZET also rectified that he hadn’t thought of selling the casts made by Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY for 100 000$ during their partnership to Gary SNELL. In fact, he wished to pawn the plasters bought from Jacques MARCOUX. Nevertheless, he ended up selling the plasters because Gary SNELL had made it a term of the contract as to avoid any competition. Robert CROUZET specified that he allegedly received the 100 000$ between April and June 1998. However, he claims that he was only paid 300 000$ for buying the plasters and that Gary SNELL, contradictory to a mail stating his intentions, never returned the plasters to him. Galia MOUSSINA explained that she had only been partially reimbursed by Gary SNELL, who declared that “nobody wished to participate”. Jacques MARCOUX stated to have obtained about 15 plasters of a value of 700 000$ from Michel TOSELLI, between 1990 and 1993, in exchange for a few paintings. According to him, in 1998, he then sold the plasters to Gary SNELL, introduced by Robert CROUZET. He affirms having never been paid by Gary SNELL. He first denied to have exchanged the plasters for paintings with Robert CROUZET. He then stopped denying it during a confrontation. At all events, the contract of the 4th of July 1998 signed by Gary SNELL only involves 5 plasters: those mentioned by the later. Jacques MARCOUX specified that the plasters were stored in the Netherlands at his ex wife’s residence and had been recovered there by Gary SNELL. Jacques MARCOUX also said that Robert CROUZET had introduced himself as Gary SNELL’s associate. Finally, he stated that both Gary SNELL and Robert CROUZET had spoken to him about a bronze editing project that were to be marked as reproductions. Michel TOSELLI confirmed that of all the plasters mentioned by Jacques MARCOUX 11 of them, that is to say 6 mentioned in the referral order and 5 not mentioned, came from his collection. Furthermore TOSELLI said he had given or exchanged them from 1994 to 1996 because he though the plasters weren’t of great value as they were workshop plasters. In fact, he asserted that he obtained them from George RUDIER a descendant of Alexis RUDIER. At the foundry’s bankruptcy, George RUDIER gave the plasters to different buyers, essentially antique dealers. However, Michel TOSELLI added that he bought the plaster “Eternal printemps” at Versailles in 1972 from Me MARTIN and the plaster “L’homme qui marche” from Me LIBERT in the early 80’s. Michel TOSELLI confirmed the origin of the plasters sold by Jacques MARCOUX, during a phone conversation with Gary SNELL. During this conversation he admitted having oriented Gary SNELL, who whished to purchase more plasters, towards Claude CUETO. Claude CUETO, a former broker in paintings and bronzes claiming to be an expert in American courtrooms, admitted to have sold 24 of the 25 plasters mentioned by Gary SNELL for the sum of 550 000$ paid throughout December 1999 to February 2001. He said not to be able to recall the last one: “L’enfant au lézard”. He concluded that the price aforementioned demonstrated that those were in fact “casting plasters” and not “original plasters”. Claude CUETO argued without any evidentiary support that he obtained the plasters from Jean MAYODON, a renowned ceramist, deceased in 1990, he introduced as Eugène RUDIER’s testamentary executor, one of the smelter of RODIN bronzes. The investigation showed that Jean MAYODON wasn’t Eugène RUDIER’s testamentary executor but his widow’s, Adolphine LAMOTHE. Claude CUETO, who denied any participation in the alleged facts indicated that the plasters stored in Belgium since 1998 had been recovered there by Gary SNELL. According to the expert: “during his lifetime, Auguste RODIN hasn’t given or sold plasters. This means that most of plasters circulating in the private domain are either overmouldings of original plasters, ancient or recent artists proofs or are a result of embezzlement of authentic plasters. The sculptor being already suspicious of embezzlement made it clear to the smelters that the models, plasters and casts remained his property.” Nevertheless, even if the RODIN Museum, claimed the ownership of the casts coming from the RUDIER foundry on the grounds that it should have restored the casts to Auguste RODIN or to the museum. The RODIN museum admits that not all of the plasters were illegally detained by private individuals, because Auguste RODIN himself had sold some plasters during his career. Gary SNELL and the GRUPPO MONDIALE company explained, during the introduction of the different exhibits they organised, that in their endeavour to make a limited edition of high quality posthumous bronzes using authentic plasters from Auguste RODIN, the plasters, after having been used, had been sold to the MACLAREN ARTS CENTER MUSEUM in CANADA. The Canadian institution admitted to be in possession of 52 plasters that still legally belonged to private Canadian citizens but are subject to fiscally advantageous donations. During this process, before being declared as “Canadian cultural assets”, the plasters have been subjected to an expertise in CANADA. The designated expert, Jacques DE CASO, without talking of the notion of authenticity estimated that the plasters, qualified as “foundry plasters” contrary to the notion of “first plaster” and “sole plaster”, most likely came from the RUDIER foundry. The expert considers that the foundry plasters are “transitory artefacts and commercial objects” that should be seen in a pejorative or derogatory manner. Finally, the expert concluded that it was in the Canadian museum’s best interest to accept the donation. For it’s part, Gary SNELL said to the investigating judge that he hasn’t seen any of the plasters which he himself calls “foundry plasters” since 2000, when they arrived in CANADA. He adds about the ulterior mouldings: “we had no need of the plasters anymore because we had casts made from those plasters. There was no duplication of the casts”.

At his hearing, Gary SNELL explained that the sales offered by GRUPPO MONDIALE, owner of the sculptures, weren’t suggested as part of the contract, signed in May 1998, which involved not only the sale of 16 plasters but also the production of bronzes. He explained that the contract hadn’t succeeded and the parties contributions had been refunded. This statement was confirmed by Galia MOUSSINA.

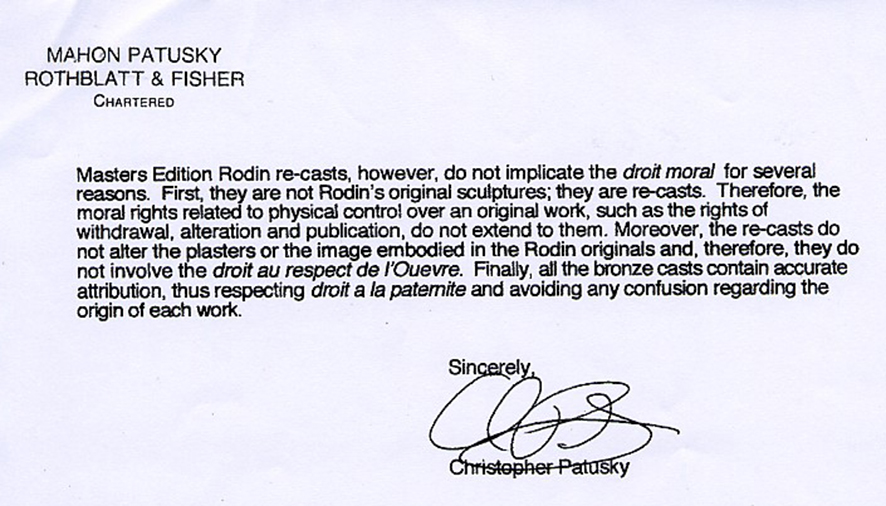

The study of the accounts of the GUASTINI foundry indicated that most of the sales of litigious masterpiece moulded there happened in the US. The bills showed the participation of the RODIN INTERNATIONAL company, located in Miami, of which Robert PREISS is the administrator. This company managed the website www.rodininternational.com dedicated to the sale of RODIN bronzes. The investigations led in the GUASTINI foundry made it possible to note the exportation of 254 litigious masterpieces from ITALY to SLOVENIA in 2002. The pieces were stored for 3 years in custom withholding by the MEDIASPEAD company in Koper. The 11th of August 2005, the Slovak authorities indicated that this merchandise had been taken into account by a company from LIECHTENSTEIN and delivered in SWITZERLAND the 19th of August 2005, to be exported to the US. The litigious pieces have been seized before being restored to the Fiduciary company CORPA TREUHAND AG representing the foundation “Basilhall Stiflung”. GRUPPO MONDIALE exhibited and put up for sale, including on it’s website located abroad, www.rodin-art.com, bronzes and plasters introduced as authentic RODIN pieces. A leaflet presented the offers in this way: “ This collection of RODIN plasters has been gathered over the years with the intention to create a limited edition of high quality bronzes. In fact, with the help of the best craftspeople and the use of the best techniques developed by RODIN smelters, the bronzes have been moulded with an extreme attention to details, dimensions and the patinas showed by the mouldings realised during the artists lifetime, under his supervision. The mouldings made during the artist’s career have been studied for this purpose. The plasters selected are those which retain the same details and qualities of RODIN’s best work. Most of the pieces of this collection come from the RUDIER foundry in Paris. The original collection is a serie of 50 RODIN sculptures. Each of them is created in only 24 copies and coupled with a certificate of authenticity. This document guarantees that the bronze as been moulded using the “Lost-wax” technique from an original plaster executed by Auguste RODIN. This certificate is attached to the bronze it concerns: it must follow the piece every time it is transferred and won’t be reproduced. Each bronze is finished with exactly the same patinas and techniques than those used during the artist’s lifetime. All of the dimensions and details correspond to the artist’s criteria in every way. Each moulding is marked with the stamp “masters limited edition” and is numbered. The aim is to put on the market the reedition of the most significant of RODIN’s bronzes using original plasters. The website is a part of the project but it will become one of the many instruments available to gain access to RODIN’s art.” The book published to accompany this “collection” introduces 22 plasters and 22 bronzes. Yet, it doesn’t give any particular information concerning the bronzes. It only mentions the dates of creation of each plaster from 1862 to 1917. The same indications can be seen on the website. However, the director of the GHI MEI museum in TAIWAN indicates in a mail dated from December 13th 2000 and sent to the management of the RODIN museum that Gary SNELL allegedly talked to him about copies of authentic RODIN pieces. Conversely, Davis WRIGHT TREMAINE, claiming to be a representative of the COSMOPOLITAN IMPORTS LTC company located in the state of WASHINGTON explained in a letter dated from the 24th of August 2001 and addressed to the RODIN museum that the GRUPPO company allegedly introduced the sculptures as being made using plasters created by Auguste RODIN himself.

Gary SNELL denies the number of 1710 bronzes calculated by the expert and estimates only 700 bronzes moulded. He reduced that number to 500 during the audience including 50 non-finished bronzes. He also believes that the prices were very reasonable and far from the prices of the authentic masterpieces of Auguste RODIN. Nevertheless, Hazel SECCOMBE HETT explains in her complaint against her associate Gary SNELL that she came to an accord with him on the sale of the plasters and the bronzes presented as authentic RODIN pieces of a value of 2 million dollars. She explained to the Italian investigators that the pieces were accompanied by a certificate of authenticity written by David SCHAFF and that she had paid them 1,2 million dollars. Gary SNELL confirmed the existence of this transaction without specifying the reality of the price given by Hazel SECCOMBE HETT. At the audience, he indicated that Hazel SECCOMBE HETT intervened during the transaction with the MACLAREN CENTER, which was supposed to buy the totality of the production to organise sales exhibitions for funding. In a mail addressed to the investigators, David SCHAFF explains that he isn’t an expert in the French meaning of the word and that all the documents he made, all destined to the MACLAREN CENTER, are in no way to be considered as “certificates of authenticity”. There are but a private evaluation without any official value destined to the Center’s curator. The procedure lasted for more than ten years. The French state was condemned because of the length of the procedure. Because of this, the court deemed it necessary to answer all of the arguments developed by the parties during the debates, including those that are redundant, to guarantee a complete judgement in which all of the positions and arguments have been exposed and argued. 1) Preliminary discussion: the referral to the tribunal. In regards to counterfeiting, the piece that is allegedly counterfeit must be clearly identified. The use of the term “notably” can eventually be justified when we come across a mass production that touches many masterpieces most of the time audio-visual ones. In regards to statues, even if the number of pieces that are concerned is countable, the accused has the right to know with precision what he is accused of. Therefore, the court can only consider itself competent to deal with the counterfeits of the pieces enumerated in the operative part of the referral order. 2) The notion of “original” pieces in regards to bronze sculptures. Article L111-1 of the Intellectual Property Code provides that: “The author of a work of the mind shall enjoy in that work, by the mere fact of its creation, an exclusive incorporeal property right which shall be enforceable against all persons. This right shall include attributes of an intellectual and moral nature as well as attributes of an economic nature, as determined by Books I and III of this Code … ». In it’s article L112-2 7°, the Intellectual Property Code provides that: “The following, in particular, shall be considered works of the mind within the meaning of this Code: works of drawing, painting, architecture, sculpture, engraving and lithography ». The caselaw always considered that for a work of the mind to be recognized and protected by the law it had to have an original characteristic even if it’s one of those enumerated by the article L112-2 of the code aforementioned. This “originality” needed to protect a work of the mind must not be confused with the notion of “original piece” as opposed to a copy or a reproduction, the only notion that is in interest here, as nobody doubts the “originality” of the works attributed to Auguste RODIN. When an artist carves a sculpture in standard materials such as marble, stone or wood, there is only one original sculpted by the artist. Every copy falls under the regime of reproductions. The article L122-3 of the same code states that: “Reproduction shall consist in the physical fixation of a work by any process permitting it to be communicated to the public in an indirect way. It may be carried out, in particular, by…casting ». The article L 122-4 specifies that: « Any complete or partial performance or reproduction made without the consent of the author or of his successors in title or assigns shall be unlawful. » as long as the goods haven’t fallen into public domain. The article L335-3 indicates that: « Any reproduction, performance or dissemination of a work of the mind, by any means whatsoever, in violation of the author’s rights as defined and regulated by law shall also constitute an infringement. » However, a bronze sculpture, which involves a third party, the smelter, after the making of the sculpture, most of the time made of earth, and one or a few elastomer plaster casts allows infinite editing even after the artist’s death. In fact, the making of a sculpture is divided in 4 stages. The first stage consists in the creation of the original plaster. The artist creates the original piece using his material of choice, most of the times earth. Then, a print is made of this creation. This print, or hollow cast is then destroyed is used to create the original plaster. This original plaster is unique and extremely precious because the piece made of earth doesn’t usually last long. Therefore, this original plaster is duplicated using a reusable cast, to create a plaster cast. The second stage consists in the making of the wax print. Using the plaster cast, a second cast is created. It is in this casts that is poured the liquid wax. A hollow bronze in obtained with this process. It is necessary to place in the wax a core of refractory material which presents the principals features of the sculpture. The thickness of the wax corresponds to the thickness of the desired bronze. This cast, as the plaster casts it originates from cannot be used indefinitely. The third stage corresponds to the creation of a “moule de potée”. After the pose of sticks allowing the disposal of fluids the “test sculpture” of wax is covered of a fine refractory material able to cling to every details of this “skin”. Another layer is added using a more skimpy material that constitutes the foundry cast able to sustain the high temperatures of the molten alloy. During the fourth stage, the foundry cast will be subjected to temperatures of 200 and 300 degrees so that the interior wax melts and flows out of the sticks. Afterwards, the cast will be baked at 600 degrees, which will harden the casts and the core. Finally, the molten alloy is poured in the foundry cast in the space previously occupied by the wax. When it has cooled down, the foundry cast is hatched to deliver the bronze. The core inside the bronze is then taken out bits by bits before the finishing touches on the patina. A bronze sculpture is always, technically, a reproduction. The strict application of the article L122-3 should lead to a sculpture never being seen as an original piece. However, most of the time, the making of a sculpture of bronze or any other metal is the ultimate goal of the artist when he first makes the earth model before the bronze casting. The importance of the sculptor’s artistic will means that despite the technical “reproduction” characteristic, the sculpture can still constitute an original work as it is understood by the intellectual property code. This interpretation is even more true, knowing that the artist intervenes after the moulding to work on the chiselling and the patina of the final sculpture. During Auguste RODIN’s lifetime, until 1917, there was no statute limiting the number of original bronzes. The historical study shows that the first reproductions and reductions were edited in large supply during the artist’s life. And if, in rare cases, the sculptor has destroyed the original cast to insure the exclusivity of the sculpture to his client, most of his work has been edited more than 12 times, the limit set by the new French legislation. Auguste RODIN gave no instruction concerning the distribution of his work after his death notably on the possibility to multiply the reproductions using the casts he donated to the French state. He only specifies that he reserves the right of reproduction and will be limited to 10 reproductions. In a letter dated from September 1916, addressed to the first museum’s curator, he indicates that he wishes, if it is possible, that the pieces that only exist in plaster be made in bronze. Yet, a book published in 1931 by William ROTHENSEIN indicates that, on the course of a conversation, Auguste RODIN allegedly insisted that he didn’t want people he had given plasters to, to make reproductions of his work. From 1919 to 1939, the museum exploited RODIN’s work without limits in regards to the reductions and only limiting itself to 12 or 25 copies for the most famous masterpieces. The code of literary and artistic property contains no definition of what is an “original piece” in the case of such replicable pieces. It is the fiscal legislation that first defined “an original piece”. In fact, the article 71 of the annexe of the French General Tax Code following a decree dated June 10th 1967 “are considered as originals; sculpture casts limited to eight copies controlled by the artist or his beneficiaries”. We will note that the word “original” has disappeared from the actual version of the statute, the article 98A of the tax code following the decree dated February 17th 1995. The 1967 decree is the first text in French legislation to limit the number of copies. Before, there was no limitation except the artist’s self-imposed limits. After a few changes, the Court of Cassation” decided in a decision dated from the 4th of may 2012 that “only the bronzes, casted using a plaster or earth model, of which the number of copies is limited, made personally by the sculptor, resulting in the fact that the work wears the artist’s print and can be distinguished in this way from a copy are considered as originals.” A difficulty forgotten by the jurisprudence is that on a technical point of view, according to the Rodin Museum’s first curator, quoted by the Canadian expert: “a casting model doesn’t make more than 5 bronzes. The cast must be replaced to insure the quality of the product. In the same way, the cast used to make the model deteriorates over time and has to be replaced.” The “original plaster” is never used to create the foundry cast. Intermediate plasters called “foundry plasters” are always made to create a piece. This explains why the notion of “original piece” regarding bronzes is purely fictitious. It is even more so since the new legislation that accepts this notion, even for a bronze made after the artist’s death. The decree of May 3rd 1981 states that “Any facsimile, aftercast, copy or other reproduction of a work of art or collectable must be described as such. Furthermore, any facsimile, aftercast, copy or any reproduction of an original work of art executed after the decree of March 3rd 1981 came into force must be marked ‘Reproduction” in a visible and indelible manner.” However not to respect this text is a contravention and the lack of any mention doesn’t characterise a counterfeit especially when the copyright fell into public domain and isn’t protected by the artist’s moral right. The legislation has changed with the arrival of the European directive on resale rights. In fact, the article L122-8 of the intellectual property code specifies that: “the notion of original piece corresponds to the pieces created by the artist himself or a limited number of copies also made by the artist or under his supervision”. The article R122-3 says that: “a limited number of copies made by the artist or under his supervision are considered as original pieces as interpreted by the previous paragraph if they are numbered, signed or duly authorized ” The enforcement of this legislation combined with the disappearance of the term “original” from the General Tax Code allows us to consider that only bronze sculptures made from an original plaster, made by the artist or under his responsibility in a limited number, can be seen as “originals” themselves. In the present case, Gary SNELL and the GRUPPO MONDIALE company have been referred for having violated the name of Auguste RODIN and the artistic identity of his work by: - The editing of too many reproductions of bronzes with details differing from the originals. - Copies not strictly identical to what the artist had agreed to. - Copies made with a plaster not made by the artist himself. - No visible and indelible mark of the mention “reproduction”. Because of the artist’s death and the fact his work fell into public domain in 1987, his moral right alone is particularly protected. The articles L121-1, L121-2 and L121-4 of the intellectual property code distinguishes 4 prerogatives that constitute moral rights that is to say: “disclosure rights” and “right to rescind” that do not impact this case and on the other hand “right of integrity of his name, his capacity and his work”. This inalienable, intangible, perpetual, imprescriptible right is enforceable against every third party. It’s aim is to protect the artist’s personality as his work reflects it. To cause prejudice to the work is by extension to cause prejudice to the artist’s personality. This moral right must be enforced even though the other rights the artist has on his work fall into public domain after some time. The simple act of making a reproduction of a piece, fallen into public domain, isn’t in itself an infringement of the moral right and therefore not a counterfeit. In the absence of a visible and indelible mark of the term “reproduction” doesn’t infringe the moral right as long as it clearly derives from the context that the reproduction isn’t an original piece. The fact of having casted pieces using a plaster that hasn’t been made by the sculptor isn’t in itself an infringement of the moral right and therefore not a counterfeit. To agree on the contrary is to forbid a third person from reproducing Auguste RODIN sculptures, most of the original plasters belonging to the RODIN museum. The prejudice against the moral right can be caused by an unfaithful reproduction of the artist’s work or the fact that the reproduction is said to be an original. The expert nominated by the investigating judge has examined multiple times bronzes and plasters kept in ITALY or CANADA. The defence criticizes not only the content of this expertise but also the expert’s personality. In fact, it believes that the later was in close contact with one of the accused, Robert CROUZET to the point that he is said to have sent him elements of the case, usurped a university qualifications and to have been convicted for counterfeiting. On this last remark, the decision issued on February 22nd 2002 by Paris’s Court of appeals declares that Gilles PERRAULT was convicted for having infringed the moral right of a person on an exhibition leaflet not on a sculpture. The decision doesn’t specify, contrary to what the defence says, that the statue in question in the case if a fake. About the university qualifications, Gilles Perrault gave an explanation that the court hasn’t been able to overturn. About the relationship with Robert CROUZET, it is undeniable that the expert maintained amicable relations with the later. The existence of this relationship, as it appears in the case, should have led the expert to end his mission as to avoid any accusation of a potential conflict of interest. Furthermore, the circumstances described by the expert to explain in what way Robert CROUZET might have been able to have access to some elements of the case or to help third parties bewilders the court. The expert’s participation in those acts is, without a doubt, a professional misconduct or even a criminal offense. Yet, can it be said that the expertise as it has been made doesn’t have any value? Is has to be said that Robert CROUZET’s involvement in the plasters whereabouts is not once minored in the expert’s report. Therefore, the criticisms against the expertise, even if they are relevant, don’t justify the swift dismissal of a long and costly expertise. From a technical point of view, the expert explained his approach on the search for traces linking the bronzes to different types of casts. For each of the litigious pieces, the expert drafted a technical sheet resuming his arguments. This approach makes it clear that most of the bronzes made by the GRUPPO MONDIALE company don’t feature a reproduction quality ensuring that the artist’s moral right was respected. Yet, Gary SNELL and the GRUPPO MONDIALE company insisted that in their exhibitions as well as in the book or the website made to accompany those and the sales expected because of the bronzes quality led the buyer to believe they were very old. In fact, they said the bronzes were faithful to the artist’s original pieces and even made from original plasters, the company also played with the ambiguity of the word “original” as they dated the exhibited plasters. As an example, the introduction to the Venice exhibition explained that: “about 40 pieces in bronze of the artist’s most important work will be exhibited, most of them in small or larger copies, with a little collection of photographs retracing their history. This is the biggest exhibition of bronzes and their corresponding original plasters in the world with the exception of the RODIN museum exhibition in Paris. GRUPPO MONDIALE EST published a catalogue of the pieces exhibited, it has been printed by Amilcare Pizzi with the help of private individuals. The photographs have been made by Mario Carrieri, considered to be the best sculpture photographer. The book traces the history of the plasters and bronzes issued from them. It confirms the high quality, veracity and the importance of this Rodin collection.” Considering the French legislation, it appears that the facts of deceit and misleading commercial practice are established. The issue in this case is whether the French legislation is applicable or not. As from the moment Gary SNELL and the GRUPPO MONDIALE company were charged, they denied the jurisdiction of the French Courts regarding the offenses of counterfeiting, deceit and misleading commercial practice. Two articles from the Penal Code were raised to back the French Courts jurisdiction in this case. Article 113-7 of the Penal Code provides that: “French Criminal law is applicable to any felony, as well as to any misdemeanour punished by imprisonment, committed by a French or foreign national outside the territory of the French Republic, where the victim is a French national at the time the offence took place." Article 113-2 of the same code states that: “French Criminal law is applicable to all offences committed within the territory of the French Republic. An offence is deemed to have been committed within the territory of the French Republic where one of its constituent elements was committed within that territory.

Nobody denies that the potential victim of the facts of counterfeiting denounced in this case is the RODIN museum located in Paris. A simple application of the article 113-7 should assess the French Courts jurisdiction in this case. Nevertheless, the articles 5 and 6 of the Berne Convention dated September 1886 specify that “the extent of protection, as well as the means of redress afforded to the author to protect his rights, shall be governed exclusively by the laws of the country where protection is claimed. ». It means, according to the caselaw of national and international courts, the country where the litigious acts have been committed. A decision issued by the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court of Appeal on November 29th 2011, reminds us that as article 113-7 is contradictory to the Berne Convention, it can’t be applied regarding the offense of counterfeiting. Yet, the caselaw admits that if the wrongful acts have been committed in different locations, French law can be applied if one of the offenses was made inside the national territory. It’s not obvious that this notion of “wrongful acts” is assimilable to the notion of “facts constituting an offense” referred to by the Penal Code. It’s even allowed to interrogate oneself on the compatibility of this article to the international Berne Convention as it is a way to contradict the later on the proper jurisdiction in a case of counterfeiting. It is not necessary to settle this debate. In fact, the different elements brought forward in order to demonstrate France’s jurisdiction in this case have been rejected by the courts. The first element brought forward was about the provenance of the plasters. The prosecution maintains that the plasters bought from Robert CROUZET came from the RUDIER foundry. Yet, it doesn’t appear that the purchase of the plasters suffices to constitute an offense of counterfeit. In fact, the right to reproduce RODIN’s masterpieces being in the public domain, the simple act of buying plasters, even to make new casts isn’t a constituent element of the offence of counterfeiting. As such, the geographical origin of the plasters is irrelevant to the infraction. The court believes that if the reproduction right has fallen into public domain, the purchase of foundry plasters in FRANCE doesn’t imply the application of article 113-2 of the Penal Code. The same result goes for the casts made in FRANCE by Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY. In fact, setting aside the fact that the procedure couldn’t determine if the casts had been used to make the litigious bronzes, the free character of the reproduction of Auguste RODIN’s pieces forbids us to deem the casts as constitutive elements of the infraction. The prosecution maintains that the contract signed in May 1998 plans in article 2 for the constitution of a company to produce and market “some RODIN sculptures internationally”. In article 3, that “Robert CROUZET will provide 16 old plasters to the company the list of which is included in the contract. In article 3.5, that Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY promises to supervise the production of the RODIN sculptures. In article 4.1 that the partners agreed to pay Robert CROUET the sum of 600 000 $ for all rights, titles and interests in all the plasters enumerated in article 3.3” and allows the later to “retain 10% of the company’s profits coming from the sale of RODIN’s sculptures before any payments or missing payments of the plasters enumerated in article 3.3” as well as “30% of the list price along with the 10% benefit aforementioned”. The contract characterized the intention of the contracting parties to produce and sell not reproductions but original RODIN masterpieces internationally. Furthermore, this contract stipulated that it should be interpreted “in accordance with the laws of the Republique and on French jurisdictions”. This information made it possible to determine that if the project had been realised, the French law would be applicable to the dispute and the French jurisdictions would be competent to hear it. Yet, the procedure shows that the litigious sculptures haven’t been made under this contract. In fact, the investigation didn’t find that the contracting parties had received a percentage of the sale of the bronzes. Neither Robert CROUZET nor Bernard POISSON DE SOUZY or Galia MOUSSINA have been prosecuted for counterfeiting because they had signed the contract. It appears that none of the elements brought forward by the prosecution, the investigating judge or the public ministry is enough to recognize the competence of the French court or the application of article 113-2 of the Penal Code in this case. The court can only note that the fabrication, the exhibition, the sale and the exportation of the litigious pieces have all been carried out outside of the national territory. As some jurisdictions have already found when dealing with cases of restitution of pieces seized abroad, the French courts are not competent to hear of the allegations made against Gary SNELL and the GRUPPO MONDIALE company. More precisely, on the three accused who sold plasters to the GRUPPO MONDIALE company, the court believes that even though this sale isn’t a element constituent of the infraction, thus isn’t an act of complicity, no element of the dossier enables to affirm that they knew of the buyer’s intention to produce piece of dubious quality not marked as reproduction.